THE Egyptians were the first to divide a day in two 12-hour periods, each of which devoted to the hours when there is sunlight and to those when it is dark. The length of these hours seems based on the sexagesimal system of time measurement — a numeral system using 60 as the base figure, explaining the number of minutes in an hour, seconds in a minute — practiced by the Sumerians around 2000 B.C.

While the Romans adopted this 24-hour day, they tweaked it to compensate for the variation in length of daylight hours during a particular season, which are longer in summer, shorter in winter. For their empire, daylight hours stretched to around 75 minutes each while dark hours were constricted to about 44 minutes each during summer. In winter, the computation was reversed.

The season’s effect on the length of daylight and dark hours is amplified with latitude. So in England, for example, an hour could last between 38 minutes to 82 minutes, depending on the season. And this practice continued well into the 14th century.

While this method of observing so-called temporal hours presumably proved effective to an extent — well, it was in place for hundreds of centuries — it was also becoming necessary during this period to devise a more standardized and precise way to keep time. Cities in the 1300s were increasingly beginning to get industrialized, for one thing, and commercial trade between them was flourishing as well.

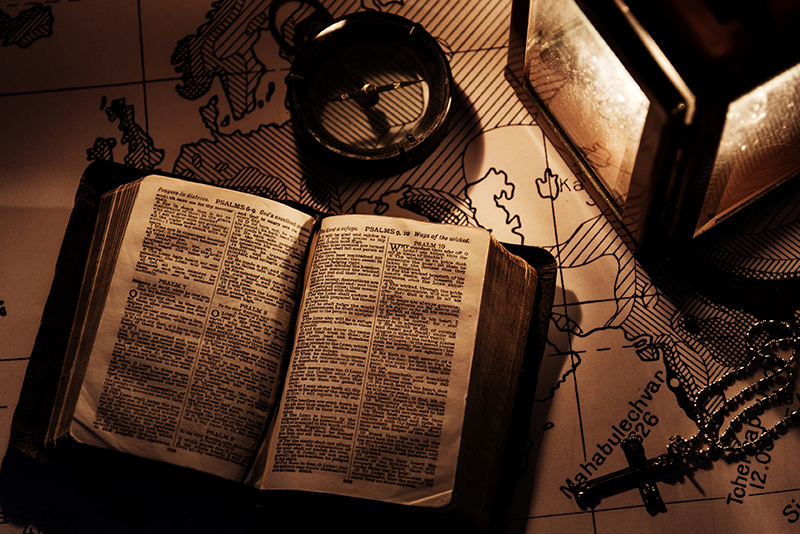

Preceding this development, however, was Christianity’s need not only to mark the seasons (in order to determine, for instance, when Easter falls) but also to ascertain more accurately the canonical hours within a day.

These canonical hours are the seven prescribed times in a 24-hour day during which specific prayers have to be said — “Seven times a day I praise you for your righteous laws,” it is written in Psalm 119:164. The practice, thought to have originated from the Jewish, spread throughout the centuries as it was passed down to various civilizations. Eventually, a specified time and common liturgical formats began to emerge.

Christians continued the practice, specifying the Psalms and the Lord’s Prayer to form a part of the canonical hours. Prayers in the morning, evening, the third, sixth and ninth hours were later on prescribed. By the end of 300 A.D., the standards governing canonical hours have largely been put in place.

In the Catholic Church, where the canonical hours are also referred to as offices — the official set of prayers for the church — the rituals observing canonical hours grew more elaborate, requiring various books. A standard format of the daily prayers, called breviary, was developed, which by the14th century contained the entire text of the canonical hours.

While the texts contained in the prayers were revised numerous times up until the 21st century, what remained constant are the frequency — seven — and the time at which prayers have to said. The schedule prescribes dawn, first hour (6 a.m.), third hour (9 a.m.), sixth hour (12 p.m.), ninth hour (3 p,m.), sunset and before bedtime (the Office of Readings must also be said at any point in the day).

Fortunately, mechanical clocks started appearing in the late 13th century and the early part of the 14th century. The device was a natural fit at following the sexagesimal system and also lent itself well to dividing a day into 24 equal units. This allowed for trade and commerce schedules, as well as spiritual duties, to be more precisely and reliably followed. Suddenly, water clocks, sundials, hourglasses, candle clocks and similar time-telling contraptions just would not do anymore. With mechanical clocks, official duties, pertaining to both workplaces and prayers, could be performed on time, all the time.

As history shows, mechanical clocks improved vastly over the centuries as they employed the pendulum, the mainspring (which opened the door for portable clocks and, eventually, pocket watches), and the balance spring, among other innovations. By the time the 20th century rolled around, the clock (and all sundry timepieces) had become more accurate and sturdy than ever — a development that really never let up since.

In the 21st century digital age though, in which other timekeeping devices (like those built into smartphones) have turned significantly more precise and accessible, we can only reflect at the key role mechanical clocks and similar timepieces have played in the performance of offices (referring, again, to industry and canonical hours) throughout the centuries. And, yes, we can pray for their continued existence, too.