Sometimes, people make history. In this case, a plane did as well.

Bremont has released a limited-edition watch called the Comet DH-88. It’s a commemorative piece that pays tribute to a great air race that happened in the 1930s. It had a commercial foundation, but the story it gave us is an inspiration to us all, and Bremont is helping us to remember.

In the 1930s, flight was not the ubiquitous mode of transport that we take it for today. International air travel was no small undertaking, and spanning the globe was a thing that even the most experienced pilots found daunting. Consider the flight from England to Australia. It was possible, yes, but it wasn’t easy. And it certainly wasn’t fast.

The first successful flight from England to Australia happened in the year 1919. It took, well, weeks. Let that sink in, if you will: it took almost exactly four weeks, 27 days and 20 hours. A pair of brothers named Smith did it, but we’re not talking about a clean, clinical process here. When I say that it was done successfully, I mean there were a lot of unsuccessful attempts along the way, and as you know, unsuccessful endeavors in airplane flights often end, well, abruptly. Sometimes terminally. No pun intended.

By the year 1934, repeated efforts had brought that flight time down from four weeks to just over seven days. It was now taking seven days to fly to Australia. But people wanted that time lessened even more. One of the goals was to prove that it was feasible commercially; that you could actually have a fast (and safe) commercial air route from England to Down Under.

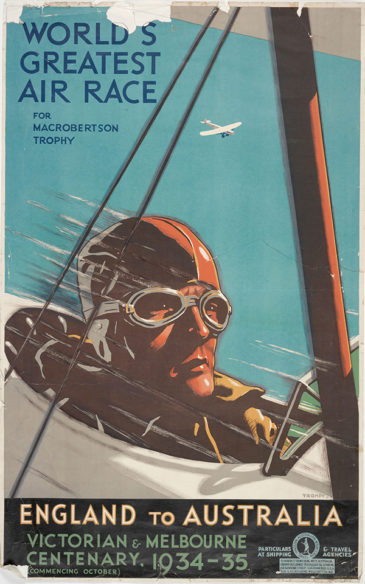

The Macpherson Robertson Air Race was created to do just that; to show the world that the flight could be done faster. And several teams from many nations took up that challenge, in an event that would be termed ‘infamous’ and also called ‘the greatest air race of all time.’

Was it? Bremont thinks so, and they want to tell the world that story anew. In 1919 a pair of English brothers flew the route for the first time. Now, decades later, another pair of brothers is working to both remember the Macpherson Robertson Air Race, and to aid the remembrance of aviation in general.

Nick and Giles English, the founders of the Bremont watch company, have released the DH-88 Comet Limited Edition wristwatch, a chronometer-level chronograph watch that serves as a fitting and stunning reminder of the greatness and perils of aviation. The English brothers know that world well; both of them are pilots, and their own father perished in an air crash that also left one of the brothers severely injured. Yet their love of flying, and of the history of aviation, remains undimmed. The release of the Comet watch will also help raise funds for the Shuttleworth Collection, a unique collection of functional flying aircraft. The Shuttleworth Trust has over 40 craft, and some of these planes are the only flying examples of their craft still in existence. Indeed, the DH-88 airplane that this watch is named after is the only flying DH-88 left in the world… and it just happens to be the one that won the race in 1934.

But what was that race? What was so difficult about it, what did it take to fly it, and what kind of plane was it that pulled off the win?

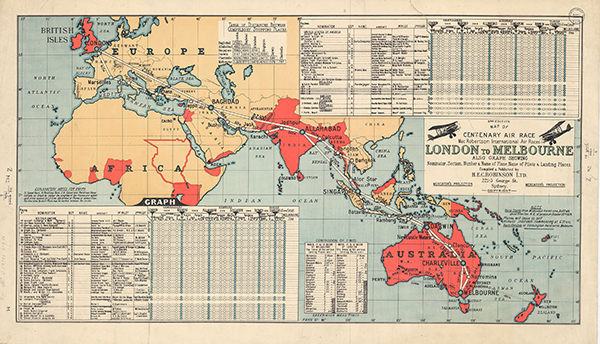

Sir Macpherson Robertson was an Australian businessman, and he made no bones about what kind of air race wanted to sponsor. “Make it the greatest race yet conducted in the world,” were his instructions, and maybe it was. Twenty airplanes from six nations would join it. Five compulsory control points, 11,300 miles, and a £10,000 prize for the victor.

The race announcement alone created a sensation when word first passed around. Pilots sought sponsors to build them airplanes that could make the arduous journey; there was no limit placed on airplane size or power.

The English aviation community quickly realized they had no airplanes capable of performing competitively. It was feared that an American transport plane would sweep all British competition aide. Unable to stomach the thought, British magnate Sir Geoffrey de Havilland proposed to design and build a plane that could fly and win the Macpherson Robertson race.

He created the De Havilland-88 Comet, a streamlined twin-engine plane with Gipsy Six engines and a spruce-plywood body. Within weeks three orders for the Comet were placed. The plane had a cruising speed of 220mph and a range of 2,900 miles. The three Comets would be competing against each other, as well as the rest of the field, which included an American Boeing 247D, and a Dutch KLM Douglas DC2. The Dutch flew “immaculately uniformed” airline pilots, and carried three passengers and a bag of mail.

One of the DH-88 Comets was purchased by Albert O. Edwards, the managing director of London’s Grosvenor House Hotel. He named it Grosvenor House, and it was painted racing red. It would be flown by pilots Charles W. A. Scott and Tom Campbell Black.

Bremont’s new commemoration watches. Each contain some of the spruce plywood used in the original “Grosvenor House” de Havilland Comet.

From England to Baghdad, through Allahabad and past Singapore, the Macpherson Robertson Air Race made its checkpoints and sped towards the Southern Continent. The perils of the race were demanding, the pace relentless. At one point the Boeing nearly flew into a mountain. One of the Comets, Black Magic, got lost and landed in a far-off filed with empty fuel tanks. They refueled from a bus station and flew on. In the end, their race ended when six engine cylinder heads and their pistons burned out.

And halfway across the Sea of Timor, the port engine of Grosvenor House sputtered and died. They landed in Darwin with one working engine and a new record time. Two hours later, their engines running rough but both functioning, they took off again.

When Grosvenor House landed in Melbourne, they were the champions, completely exhausted, and had a final time of 2 days and 23 hours. Pilots Scott and Black had speeches and handshakes, and then finally a well-earned rest. They had done the England-Australia run in less than half the time record, and they and their aircraft would enter history.

Today the Grosvenor House is the only DH-88 Comet still flying, and Bremont and the Shuttleford Trust intend to keep it that way.